Non mi piace rivelare "spoilers", tuttavia mi premuro di dire che la scena che sto per descrivere è tra quelle iniziali del film...chi vuole può continuare a leggere.

L'ambientazione è notturna, lo scenario una piana ghiacciata: al tempo di musica entrano nell'inquadratura delle figure completamente vestite di nero, con lunghi manti che celano completamente le forme del corpo, che sembrano uscite dal carnevale veneziano e, volteggiando sul ghiaccio, portano sulle spalle una bara illuminata al centro da una serie di candele disposte a cerchio, unica fonte di luce della brevissima scena.

La forza evocativa di tale immagine è indescrivibile a parole e fa auspicare la visione di un film in cui sia la musica a parlare ed a materializzarsi attraverso le immagini sullo schermo, un po' come nel capolavoro della Disney "Fantasia" o, per citare un esempio appena più calzante, l'ultima parte dello splendido "Amadeus" di Milos Forman.

Ahimé, non è così: il film diventa quasi da subito un esercizio di stile compiaciuto ed a tratti persino retorico, sprofondando nel non senso nel disperato e ambizioso tentativo di raggiungere la perfezione intellettuale, una teoria sui massimi sistemi autoevidente erga omnes.

I personaggi sono antipatici, logorroici e, cosa alquanto incomprensibile, data la parina di finta-raffinatezza che pervade il film, sboccati come fossero in un film sul Bronx.

Peccato per John Hurt, la cui interpretazione nei panni dell'eccentrico professore Mondrian Kilroy è l'unica punta di genuina malinconia che la pellicola può vantare ed è tuttavia sacrificata dalle parole moraleggianti messe in bocca al suo personaggio.

In fin dei conti, il tour de force filosofico di Baricco si traduce in una grande sfilata di simbolismi banali, la cui elementarità non è giustificata da un legame viscerale con la musica del maestro Beethoven che, tagliuzzata qua e là "ad effetto" alla mercé del regista, non diventa mai essa stessa un personaggio della storia, bensì rimane un accessorio fungibile.

Solo nei rarissimi momenti in cui Baricco mette da parte il suo ego ed apre uno spiraglio alla musica, rendendola unica protagonista della scena, si realizza in atto quello che il film trascina in potenza per la sua ora e tre quarti di durata: pura ed incondizionata bellezza.

A voi la scelta...

"Lesson 21" a.k.a. "Lecture 21" (U.K. title)

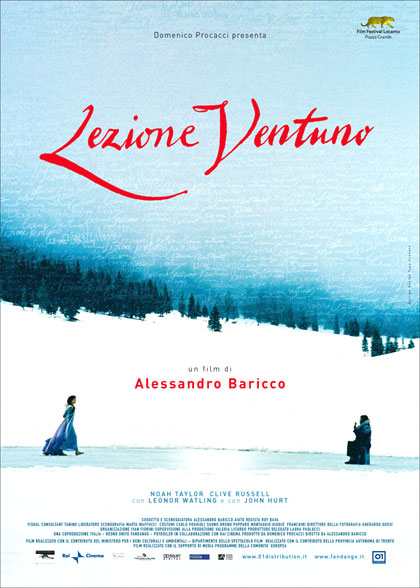

What follows is my review of the film "Lezione Ventuno", written and directed by acclaimed novelist Alessandro Baricco and first presented at the Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland last August. It opened in Italy on October 17.

I'm not exactly a spoiler lover, however I feel there is a scene in this film I must describe to get to my point. If it's any consolation at all, the scene takes place very early on in the film, so I'm sure that will soften the blow.

The scenario is a nocturnal view of a frozen plain: a small bunch of strange figures enter the frame, clad in long black mantles, as if they were coming straight out of Venice's world famous carnival, and, following the tempo of the background music, twirl harmoniously whilst carrying a coffin, at the centre of which a few candles are burning, creating the only source of light in the scene.

The image is so chillingly haunting that it leaves you dumbstruck and appears to be setting the pace for a film dominated by the impetuous and mighty score borrowed from Beethoven's impressive repertoire, imposing itself as a painter of its own portrait through the big screen.

Unfortunately, the audience is in for a disappointment: the film soon turns into practice material, a purely academic exercise set into motion by one who strives to reach intellectual perfection, pure theory concering the chief systems of existence, and instead makes a false move, trapped by self-absorption and rhetoric.

The characters are unpleasant, excessively loquacious and, what's most incomprehensible, given the seemingly glossy finesse spread throughout the whole film, really foul-mouthed, as if the audience thought they were going to see "Hustle and Flow".

It's truly a shame that John Hurt had to be involved in all of this, because even his genuinely melancholic portrayal of eccentric professor Mondrian Kilroy is toned down by the pithy lines he has to deliver.

All taken into account, Baricco's philosophical tour de force consists of nothing more than a far too carefully put together series of trivial symbolisms, deprived of a visceral bond with Beethoven's compositions, which in fact would have justified their basic nature.

The music itself, cut and patched up at the director's will in the hope making the scenes more catchy, is never given the opportunity of becoming a stand-alone character in the story and remains an anonymous and disposable accessory.

To tell the truth, it is in the extremely rare occasions in which Baricco puts aside his ego and allows a glimpse of music to shine by itself in a scene that what is dragged through an hour and three quarters without ever emerging finally takes place: pure and unconditional beauty.

The choice is all yours...

No comments:

Post a Comment